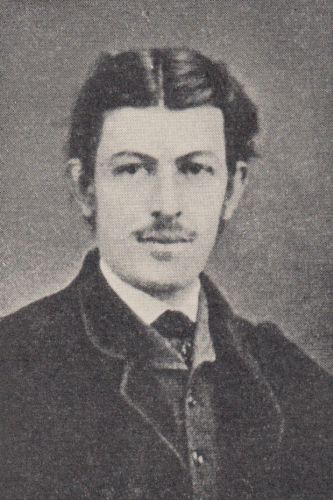

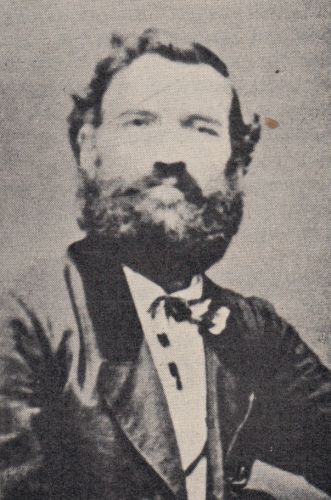

Hruschka in his major uniform (1857 - 1865). Photography ownership – Hruschka's daughters

The Hruschka's family comes from Silesia, the nothern part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His grandfather Franz Jan Hruschka was the warden of the baron Bereczky farm in Bravantice, Bilovec district. He married Jana Nepomucena of the maiden name Herrmanova from Bravantice.

Franz Ludvik Hruschka was born in Bravantice on 25th August 1787. When he finished his philosophy studies at Prague he joined up voluntarily the army on 7th July 1804 and was assigned to the Moravian Field Artillery Regiment in Olomouc. Already next year he combated around Ulm and Norimberk. He was in the military unit which bravely saved the army field cash register as well as archduke Ferdinand from the captivity. Hruschka-father was himself captured, but managed to escape and already the same year he combated around Jihlava. On 1st November 1806 he was assigned to the Artilery unit based in Vienna, with which he took part in the French war (1814-1815). He reached the Detachment Commander rank when he got married on 30th March 1818 in Vienna. His wife Anna was the daughter of the first lieutenant of the second artillery regiment Mr. Jakub Simon and his wife Eleonora. In 1819 Hruschka-father was promoted to sublieutenant rank as was assigned to the fourth Upper Austria Field Artillery Regiment based in Czech Budejovice. His son (the honey extractor inventor) was born when the family was still in Vienna. Hruschka-father combated with his regiment the Napoleon wars and in 1824 was promoted to the first lieutenant rank. He was based to Graz, Steiermark in 1827 and promoted to captain lieutenant in 1836. In 1839 he became the captain and was based to Olomouc Regiment, the very same one where he started his army career. Since 1841 the regiment was commanded by Josef Juttner, the member of the Royal Czech Association for Science, and the corresponding member of the Patriotic-Economic Association, and the honorary member of the Patriotic museum at Prague. Hruschka-father stayed there till 1844, when he was based to Hradec Kralove. In 1848 he was promoted to major rank and placed to Venezia area head quarters. He was shortly based in Verona when he finally became the commander of the eigth section of the artillery administration for Dalmatia placed in Zadar. He was promoted to the aristocracy the same year and he was not an officer of the field services. On 8th July 1857 at the age of 70 he was retired at the lieutenant colonel rank. He lived the last years of his life in the city of army retirees, Graz, where he died on 22nd August 1862, so he didn't live to see his son's apicultural fame.

Major Franz Hruschka was born on 13th May 1819 in Vienna. He lived his childhood in Czech Budejovice. He moved with his father in 1827 to Graz, where he attended the elementary school and three years of the secondary school. At the age of 14 he was drafted and as a cadet of the 19th Infantry Regiment Hessen-Homburg he was assigned to the cadet's unit in Graz. He studied the Czech language in the cadet's school as well, his Czech language teacher was captain lieutenant Ondrej Krcek. He graduated from the cadet's school after three years in 1836 and joined up his regiment which was based in Vienna. Within few days though he was re-assigned to the Hungarian regiment Bakonyi number 33, which was based in Milan. Hruschka even later on joyfully re-calls the Milan stay as "whole ten years of pleasant memories, when I dreamed my youth dreams and gained my first real-life experiences." He was promoted to the officer cadet rank in 1840 and to the lieutenant rank in 1844. The officer head quarter moved to Zadar in a mean time, but it appears Hruschka stayed in Italy. After the eventful year 1848 he joined up the marines and was promoted to the ship sublieutenant.

Since that time we have Hruschka's qualification certificate. It reads Hruschka is open-minded with great talent; he dedicated his free time and scarce funds to the construction of a device with which one can draw the landscape as well as the person faces quickly and accurately. In 1844 he came up with a boat one can power with oars as well as sails. When he was a ship sublieutenant he received a Military Merit Cross with decorations for successfull operations around Caorle during the Venezia blockade. The same year part as an artillery officer he took part in the besiege of Ankony on frigates Gueriera and Juno. He was promoted to the frigate lieutenant in 1849. Shortly afterwards – in 1850 – he married Antonia Albrech. And in 1852 he was promoted to the ship lieutenant rank.

In 1854 he receives the honorable recognition for decisive and effective commanding of the Delfin ship during the several day long sea storm. In two years however he came back to the infantry and is assigned to the Infantry Regiment Culoz number 31. He is promoted to the major rank in 1857 and is given the command of the local unit in Legnago, the small city in Verona area on the lower part of the Adige river. This event ends Hruschka's army career as on 1st August 1865, in the year of this honey extractor invention, he is retired. He took as his domicile the city Dolo in Venezia area, where he had a small farm, which was given to his wife as a dowry.

Hruschka with his wife: left his son Friedrich, in the middle his daugher Antonie, right his daughter Marie. Photography ownership – Hruschka's daughters

Hruschka met his future wife in 1848, when he was the marines officer. He anchored his boat in Trieste. After his night shift he passed the command to his first officer and went to sleep. Shortly he was waken up as two noblewomen visited the ship, countess Schoenborn and her daughter, and wanted to see the boat. So the commander was called up to be their guide on the visit. That was the beginning of Hruschka's courtship, which lasted nearly two years. At the beginning it looked absolutely hopeless. Hruschka was already higher officer at his young age however he was quite poor. Finally countess Schoenborn agreed to the marriage but she never accepted Hruschka. She hardly ever visited her daughter's family. She did send a present to kids or some household allowance from time to time, but her heart stayed closed.

Countess Schoeborn was not the real mother of Mrs. Hruschka, she was a daughter of civic parents Josef and Antonie Albrecht. She was born in Moor in Hungaria and was later on adopted by countess Schoenborn. She was nearly 25 years old when she met Hruschka. Countess Schoenborn gave her adopted daughter rather large dowry: 12 000 Guldens. Next to it the young couple got a small farm in Dolo and a house in Venezia, called palazzo Brandolin-Rota. The marriage took place in 1850. After the marriage Hruschka lived in Pula for some time, later on in Venezia. He never presented his wife on public, didn't take her to the conferences nor to the apiculture meetings, he even didn't speak about her.

So all we know about Hruschka's wife is thanks to the short notices left by the frequent Hruschka's apiary visitors. They remember her not only as a good mother, but as a noble woman by spirit and upbringing and as an excellent beekeeper, who guided the visitors around the apiary and explained everything interestingly during her husband absence. Dr. Angelo Dubini was sorry to miss major Hruschka at home, but was pleased to meet his noble wife who proved to be enthusiastic beekeeper as well. Another visitor, Luigi Giani, writes in his article to the newspaper in more details:

"Hruschka was in Venezia. The French are right however when they say: Sometime even an accident is good. When they took me to the house of major Hruschka I was honored and had a good luck to meet his noble wife. Even though I came at an unusual time, at seven o'clock morning, she came readily when notified somebody was there to speak with her husband, and was my kind guide around the beautiful garden within which are the major's hives. She told me the honey harvest for each and every hive. This year harvest was extraordinary and promises an excellent yield. Keeping bees on the detachable honeycomb system is allegedly the only way promising big things in future..." Mrs. Hruschka was five years younger to her husband and lived five years longer then him. She died on 16th January 1893 at four o'clock afternoon at the age of 69, same as her husband. She died very poor. Towards the end of her life she had to work manually to earn her living. She died in the rented place, palazzo Rizzi, in the same flat as her husband died five years earlier.

Hruschka's children. From left: Rosalie, Antonie, Friedrich, Marie. Photography ownership – Hruschka's daughters

The Hruschka couple had five children:

1. The eldest son Franz was born on 12th November 1851 in Pula. When he was 13 he went to another family for upbringing. Hruschka's daughters told us he was a post office clerk in Trieste. He died on 5th May 1922 childless. He estranged his original family.

2. Antonie, was born in 1852 in Venezia. She died at the age of 16 in Dolo in 1868.

3. Marie, was born in 1855 in Venezia. She married Emilia Moretti, they had son (born in 1882).

4. Friedrich, was born on 18th October 1857 in Legnago. He married Maria Binetti, had two daughters – Sophia and Irene.

5. The youngest daughter Rosalie was born in Legnago in 1861. She married Karl Rizziou, who was salesman. She had son George.

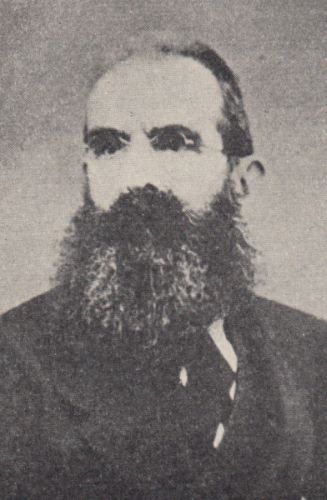

Hruschka's son Friedrich. Photography ownership – Hruschka's daughters

Hruschka was still in Legnago in February 1866, because he sends his article for the Eichstaett beekeepers news from there. The Austro – Italian war started in the same year, and after the war Legnago was annexed by Italy. Probably within the same year he moved to Dolo, as the letter to Eichstaett beekeepers news dated 12th February 1867 is signed "k.k. Major, retired, Dolo bei Venedig". He was signing his later documents the same way.

We can reconstruct the look of the Hruschka's house in Dolo, Contrada della Bassa No. 687, from the description given by his frequent visitors. The house looked a bit like a château and there was a big garden in front of it. The nothern side of the garden ended by the bank of the Brenta river, fitted with hedges. Hruschka had his own boat on the river and used it to commute to the city center. The garden paths were lined with the vine arbor. Fruit trees were in the alleys as well as on it's own. There were plenty of roses and other flowers in the garden, the rest was used as a vegetable garden. The hives of many shapes adorned the garden, they were in three main groups and in addition some of them were scattered around the garden.

The hive entrances were oriented towards east. Hruschka used to say the bees want to see the sunrise. He had his own workshop in the château, equipped with tools for wood and metal processing. Next to it he had an extra room used to hold the beekeeping courses.

It appears Hruschka was quite happy at Dolo. He was pleased he drew the attention of the whole beekeeping world those days partially as well because Dolo was just half an hour away from Mira, the place where Dzierzon got his first Italian bees. "Italy is especially well suited for beekeeping. I say especially, because I've got in front of my eyes the landscape from where the first Italian bees were exported to Germany," he says explicitly in his lecture at Dolo in 1868.

The personal contacts Hruschka established with the leading beekeeping personalities on Brno conference were partially stopped due to the Austro-Italian war and Austro-Prussian war. The Darmstadt conference was to take place in 1866, but was postponed due to the wars and was not held the next year either.

Hruschka however kept himself busy. His apiary was fixed up with the detachable honeycombs and was surely a good school for the "old order" devotees (beekeeping on non-detachable honeycombs). The Italian beekeeping was underdeveloped and was just waking up to the new life. Hruschka characterizes the current stage of Italian beekeeping as "full of superstition, foolish prejudices and total ignorance." Hruschka says that not only individuals but whole groups were coming to him to see the wonders of the new method; most of them had never seen the queen bee, and some of them didn't even know the drones. Amazed they looked at Hruschka who was working without any protective gear with the opened hive or who was showing them the lower part of the honeycomb with the bee queen laying eggs (while they were hiden in the shelter). Soon the Italian beekeeping boiled with the new life. While looking through the yellowed pages of the two oldest Italian magazines we can't stop wondering how fast Italians were able to compensate for the neglected decades and how soon they walked their own paths. Hruschka, who happend to be at the start of the modern Italian beekeeping, must be credited for his spoken and practical lectures, though his public activities started much later.

The two oldest Italian beekeeping associations were established in 1867: The central association for beekeeping progress in Milano and Beekeeping association in Verona. The first issue of the eldest Italian beekeeping magazine "L'ape italiana" was published on 15th February 1867; and it was then published twice a month.

Already in 1866 Hruschka did interesting experiments with bee colony living without the hive, it was only protected from the rain by a simple roof. During the chilly days of late autumn he brought it into the cool, yet freezeproof room with the temperature around 4° Celsius, where the colony survived the winter superbly and was still sitting quietly while the other colonies from the apiary were flying and collecting pollen from the hazelnut trees. The Milano beekeepers association held the first ever beekeeping exhibition in Italy in 5th – 8th September 1867. Hruschka however didn't take part in it. It shall be mentioned there were honey extractors constructed by engineers Franc and Karl Clerici on display, the first Italian made machines, which were much simpler, not so heavy and cheaper then the original Hruschka's machine.

Hruschka continued his experiment with the colony without the hive in 1867; by impuls from general Gorizzutti he measured the temperature in the brood area as well as in the honey stock area. At the same time he measured the temperature of the last honeycomb in the hive. The colony without the hive died in the winter probably by dysentery. The observations of the colony without the hive convinced Hruschka that sufficient supply of air is an important prerequisite of successful wintering.

Ing. F. Clerici. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

Hruschka in a meantime became known to the whole beekeeping world. It was rightly written by vicar Bastian, that Hruschka with his invention gained the finest place among beekeepers of all times. Hruschka gets an honorable membership in the Verona beekeepers association in 1868. Baroness Berlepsch wanted to give her husband an album with pictures of outstanding beekeepers of those days as a christmas present in 1867. She asked several prominent beekeepers to send their pictures to her, Hruschka including. Hruschka readily fulfilled her wish. It appears the Berlepsch couple thanked Hruschka in writing. It was probably their letter Hruschka mentions in his October article for Eichstaett news as a pleasant surprise: "While I am writing these lines I am surprised by a nice letter from far away, for once I can be mostly pleasantly surprised and I thank for it heartily." In May this year Hruschka experimented with the mating of bee queens having them attached on the cocoon fiber.

Baron Berlepsch. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

The German and Austrian beekeepers conference took place in 8th – 10th September 1868 in Darmstadt, together with the beekeeping exhibition. Hruschka took part in both events. The 13th point on the conference program was the issue, whether or not to keep the bees on the detachable honeycombs and how it's linked to the honey extraction invented by major Hruschka. The speaker for the issue didn't show up, however during the discussion vicar Koehler said that the profit the beekeeper gains with the detachable system is 1:2, and should they use the honey extractor at the same time, the gain is 1:4. Vicar Bastian used warm and persuasive words when speaking about the honey extractor when he said that where ever the Dzierzon hive is there will be Hruschka's machine as well, and it'll outstretch the whole civilised world. Hruschka contributes to the discussion about the extraction of the heather honey. He doesn't recommend the watering of the honeycombs (thus opposing the prior contribution by Deichert), but recommends the warming up the honey extractor. He thinks that in the temperatures of 24 - 30° Celsius it will be possible to extract any honey, even the crystallized one, without using water. He notices the current machine uses rather slow rotation speed, because using the higher speed would damage the honeycombs. He has on his mind a considerable improvement in this direction. The third improvement of the original machine shall be on the necessity to uncap the honeycombs before the extraction. Hruschka however didn't say on the conference what should replace the uncapping. Only later on Dzierzon revealed Hruschka had on his mind melting of the caps with the warm iron plate. The conference established the preparation board for a quarter of a century jubilee of the Eichstaett beekeepers news, which was to take place in 1969 and Hruschka was elected to it. On his way back from the conference he stoped by at Bennsheim to visit Kopp's apiary and collections. Then he visited Berlepsch couple. Baron Berlepsch had a stroke and was slowly recovering from the hard fit.

Baroness Lina Berlepsch. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

Hruschka visited the agro-industrial exhibition in Verona on his way back from Darmstadt. The exhibition was placed in Palazzo communale and surprised everybody by the quantity as well as quality of the things on display. Hruschka, who had some of his things on display as well, got the honorable recognition for the best beekeeping methods and getting the bee products.

Hruschka gave a lecture on the autum meeting of Comizio agrario di Dolo about beekeeping in Italy. In the comprehensive, possibly the largest speach he pointed out the underdevelopment of the Italian beekeeping compared to the central European countries. He thinks the reason is the devaluation of the bee products. Honey is overpowered from the food chain by the plain sugar, bee wax is replaced by stearin and other substitutes. And yet the conditions for beekeeping are so good in Italy. Should the profitable beekeeping be an art in the central Europe, then it should be just a plain entertainment in Italy. To prove it he quotes the hight prices of the Italian bee queens and the recognition the Italian bees got on the exhibitions in Paris, Vienna and Darmstadt. The main mean to improve the Italian beekeeping is good theoretical and practical education. He recommends to establish theoretical / practical beekeeping courses, similar to the ones he held in Legnago. He believes the beekeeping progress is to be supported by the state administration as well as by the inteligence, especially by teachers and priests. He ends mentioning the huge benefit the beekeeping can bring not only to individuals, but to the whole nation.

Comizio agrario di Dolo issues a statement straight after the lecture that highlights Hruschka's readiness to help with the public beekeeping courses and hopes it will be used by many of the listeners. At the end of 1868 the second beekeeping exhibition is held in Milano and Hruschka takes part on it as well. He uses this opportunity to visit Milano again, the city where he started his army career. After the exhibition he wrote a comprehensive report for Eichstaett beekeepers news, which is later translated by C. Mancini for the Italian magazine Apicoltore. There was among others a picture board with the nine most important beekeepers on the exhibition and Hruschka's picture was on it as well. The exhibition in Milano ended with a lavish banquet organized by the local beekeepers to honor the visitors expecially major Hruschka.

At the beginning of February Hruschka sends his report about the Milano exhibition to Eichstaett beekeepers news, at the end of the month he issues his article about man made honeycomb base, which is printed in both Italian beekeepers magazines and later on it's printed separately as well as an edification about the the honeycomb base the manufacturing of which Hruschka started in the meantime.

In spring this year the beekeeping courses were organized in Dolo. The Apicoltore magazine announces in its February issue that two agro-associations – in Dolo and in Ivrei – are going to organize the public beekeeping courses, Hruschka was the sponsor for the Dolo course and marquess Balsamo-Crivelli was the sponsor for the Ivrei course. At the beginning of April the board of Dolo agro-association announces that as per the resolve from 30th October of the last year the theoretical and practical beekeeping courses will take place in major Hruschka's house in Dolo. Everybody can participate in the courses regardless of their social status, education, age or gender. Theoretical courses are going to be from 15th till 30th April from 9 to 12 o'clock on Sundays and Thursdays. Practical courses are going to be daily from 1st May till the end of the spring work tasks starting from 9 am in the major Hruschka's apiary. Hruschka's notes tell us the year 1869 was unusually favorable. He observed in one of his colonies (the exact one he was not able to identify as he had many colonies in his apiary) gynandromorph bees, similar to the common bees, however having the male genitals instead of the sting. He continued with his experiments to mate bee queens attached on a fiber, where he was unsuccessfull. He observed a colony with laying workers and notes that he could see at least 5 – 6 laying workers on each side of the honeycomb. He tried a new, very simple yet very effective method to requeen. He had one colony without the hive just hanging under a simple roof, and it was doing better then the ones in hives. He used the man made honeycomb bases in larger scale that year, he bought these honeycomb bases from Dummler at Homburg and was very pleased with them. He was elected a chairman of a new beekeeping cooperative in the neighbouring city Miro. On 18th August he layed the base stone for the big brick apiary for 400 colonies. He explicitely says he's done it to celebrate today's day. And finaly he bought two original Egypt bee colonies and impatiently waited for their arrival.

Marquis M. Balsamo-Crivelli. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

Hruschka attended the German beekeepers conference in Norimberk this year. Two days before he left for the conference Hruschka decided to put on a display his colony without the hive, which developed so that together with a simple supporting construction and its own built honeycombs it weighted 42 pounds. He put it into a specially constructed crate for the transport. However the trip took full four days (given those days transportation means) and was very difficult. He changed the trains twelve times and the railway workers caused him many troubles. The colony lost nearly half the bees due to the icy wind from the snow covered Alps, cold nights and persistent rain. Nonetheless it finally reached the exhibition the day before the conference started on 13th September and in the following days it was admired by everybody.

Hruschka is enrolled in the list of attendees as a representative of the join-stock beekeepers company in Miro. The conference started with warm celebration of the quarter the century jubilee of Eichstaett beekeepers news.

Hruschka contributed couple of times to the discussions about the conference topics. When discussing the first topic about the foreign bee subspecies he defended the Italian bee and pointed out the shortcomings of the European dark bee in the climate of nothern Italy. One of the topics covered on the conference was the use of Hruschka's machine for hives of different types and sizes. Dzierzon was reporting on this. He said that there is no need for an extra honey chamber while using Hruschka's machine and the hives can be smaller. There is no need either to organize for the bees to put honey into the virgin honeycombs because one can get the same pure honey from the old honeycombs as well, them being more sturdy and thus easier to extract. The results of Dzierzon were accepted without questioning.

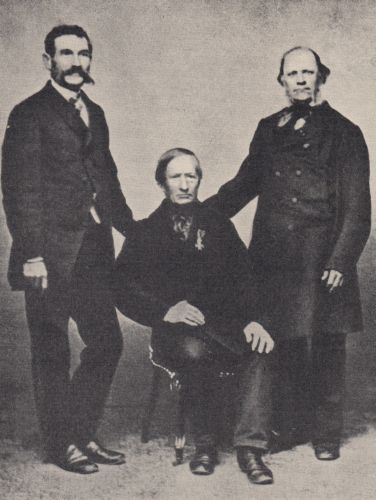

Hruschka, Dzierzon and Andr. Schmid. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

The sixth topic was about the best and safest way to requeen. Hruschka reported on this. He recommended to spray the colony and the new queen by the perpermit solution and add the bee queen without delay.

At the end of September Hruschka was in Italy again, because on 23rd September he visited the exhibition in Padova and in front of the assembled beekeepers he repositioned the colony from the common hive (with not detachable honeycombs) to the hive of his own construction. On 28th September he gave a lecture on the modern beekeeping in Padova and after the lecture he again repositioned the colony from the common hive to the detachable honeycombs system.

From 26th September to 3rd October the second exhibition of the Verona beekeepers association took place, it was in San Bonifacio in the amateur theatre and neighbouring garden. Hruschka was on this exhibition as well and he's got an honorable recognition for the lively impulses he gave by word and by example of the modern beekeeping in Venezia area.

Mr. Flachenecker, the beekeeper from Zirndorf by Norimberk visited Hruschka in the summer this year. He was the first German beekeeper who visited Hruschka's apiary. Hruschka was heartily pleased by this visit.

In 2nd – 8th December the Milano exhibition and beekeepers conference was held. The exhibition spread over four halls of the technical institute this time. There were hives (mainly with the detachable honeycombs system), honey extractors, live colonies, microscopic preparations, bee products and products made out of it on display. After the exhibition the lottery was drawn as per the German example. Concurrently with the exhibition the beekeepers conference was held in 6th – 9th December. Hruschka came to the exhibition as a representative of the permanent board of German beekeepers association and he was a member of the exhibition jury as well. The unified honeycomb frame size was set on the first day of the conference to 30 cm, Hruschka recommended that eagerly already a year ago. The size was obligatory for the whole Italy.

He lectured about the prerequisites for good wintering, about bee queens, about man made and natural swarms, about drones and about faul brood. The exhibition ended again with the common banquet held to honor Hruschka and Sartori.

In March 1870 Hruschka became the corresponding member of the Milano Assoziazione centrale. Karl Gatter, the practical beekeeper from Vienna visited Hruschka this year and comprehensively reported about it in Eichstaett beekeepers news. The German beekeepers conference was not held in 1870 for the French–German war. From now on we have only very sporadic news about Hruschka's public activities. He didn't take part in the Kiel conference in 1871, and he came late to the conference in Salzburg so the topic about the bee wintering and the shortage of the fresh air he was to report about was skipped. The Czech beekeeper Alois Thuma who was sent to the conference by the Chrudim beekeepers club have seen Hruschka in Salzburg. His article for Vcelar beekeepers magazin reads: "After a short while (we were sitting together with earl Rudolf Kolowrat-Krakowsky) ailing baron von Berlepsch and his always talkative wife / beekeeper, major Hruschka the honey extractor inventor sat next to us..." They made a toast to Hruschka on the common banquet. The conference organizors got 12 silver state medals and by the board decision they gave them to the twelve most influential beekeepers, Hruschka was among them. But this is the last note about Hruschka we have, from now on as if he drown in the see. Hruschka's apiary foreman Mr. Angelo Lettame advertises still in 1872 and in 1873 he sends two Italian bee queens to the Vienna exhibition, but these are the last news we have about Hruschka's apiary as well.

Karel Gatter. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

Hruschka towards the end of his public activities. Photo from the ZÚVČ archive

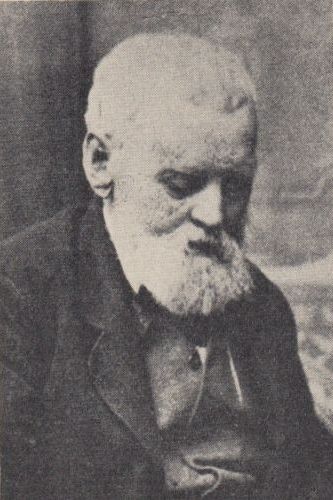

Hruschka during last years of his life. Photography ownership – Hruschka's daughters

As one can deduce from the previous chapters the year 1873 is a complete turning point in Hruschka's life. Hruschka's apiary still sends something to the world exhibition in Vienna, but that's the last news about Hruschka and his beekeeping. Hruschka left Dolo this year and moved to Venezia, where he also had a house – palazzo Brandolin-Rota, which his wife got as a dowry. Still during the first years in Venezia Hruschka kept few colonies. He gave away the rest of them. He commuted from Venezia to Dolo from time to time, but as if he's lost all his interest in bees. "He doesn't attend the beekeepers conferences and doesn't write articles for the expert magazines. The good luck he had so plentifully in past has left him."

Hruschka opened a hotel in his house Brandolin-Rota in Venezia and he rented it. And quite possibly that was the the cause of the tragic end of his life. Hruschka went bankrupt with his enterprise, possibly because of unscrupulous tenants and possibly because of less suitable location, and he never recovered from it. To save his enterprise he sells his farm in Dolo in 1880, he deposits part of his pension as well, but all in vain. Hruschka's house is sold in an auction, Hruschka moves to the rented place in palazzo Rizzi, where he died in the end. Out of despair he sells everything he had, even the gold medal he's got on the second Italian beekeepers conference in Florence for the honey extractor invention.

"The sad days of the old age came, full of disillusion, big worries, daily and never ending fight for the mere being, which were eased only by the love of his dears, till the death ended his life dedicated to the work for others." Hruschka became a silent loner; for his last six years he didn't go anywhere from his home and he didn't let his children to go anywhere either. He died in the early hours on 8th May 1888 in his flat in palazzo Rizzi in Venezia. Angina pectoris was the cause of his death. Hruschka's funeral was on 11th May 1888, with the army band and many civic as well as military attendees. His grave was not marked by any sign nor monument; it was discontinued after ten years and Hruschka's bones were put in a common pit.

Such is the fate of big inventors...